LOCATION AND URBAN DATA

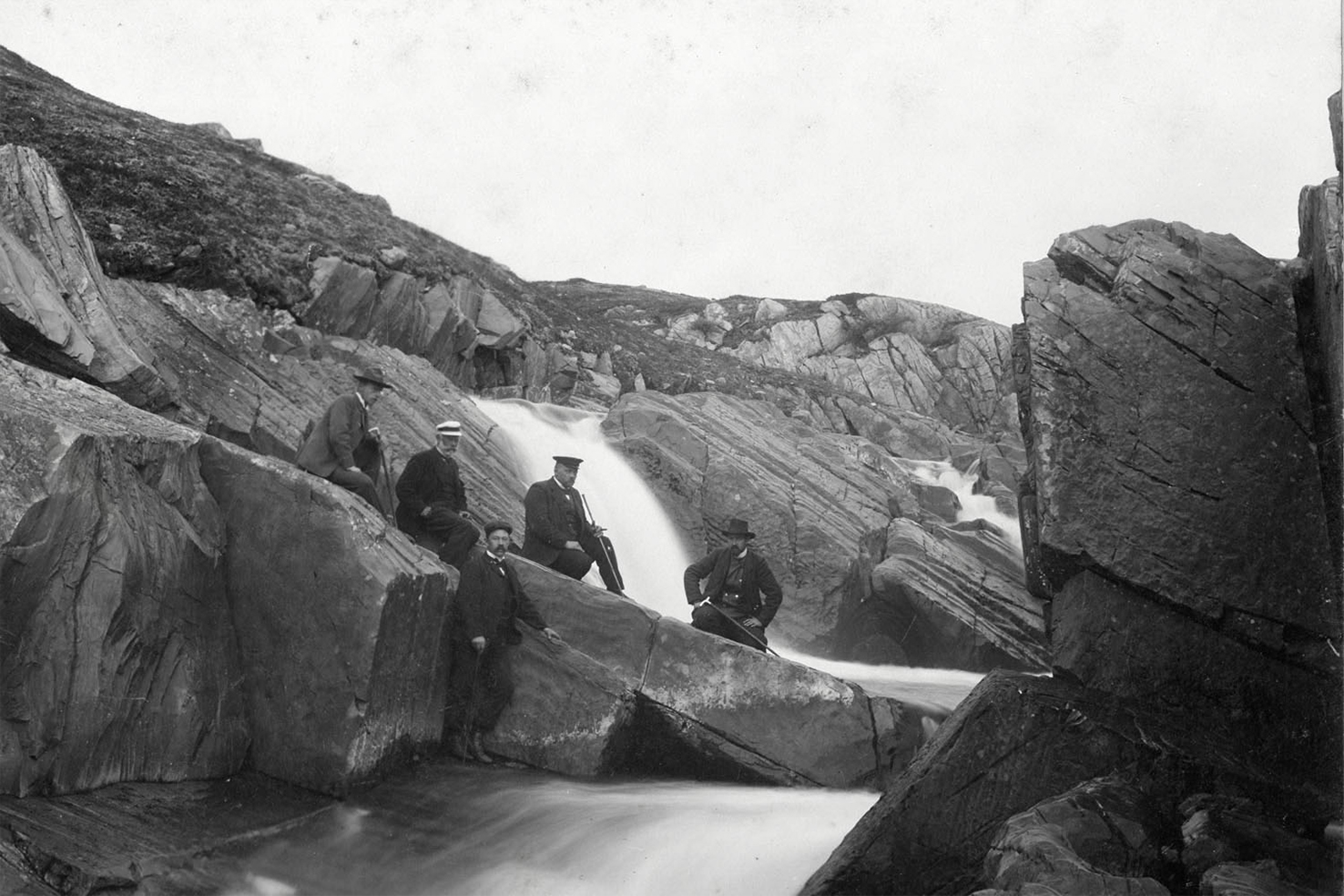

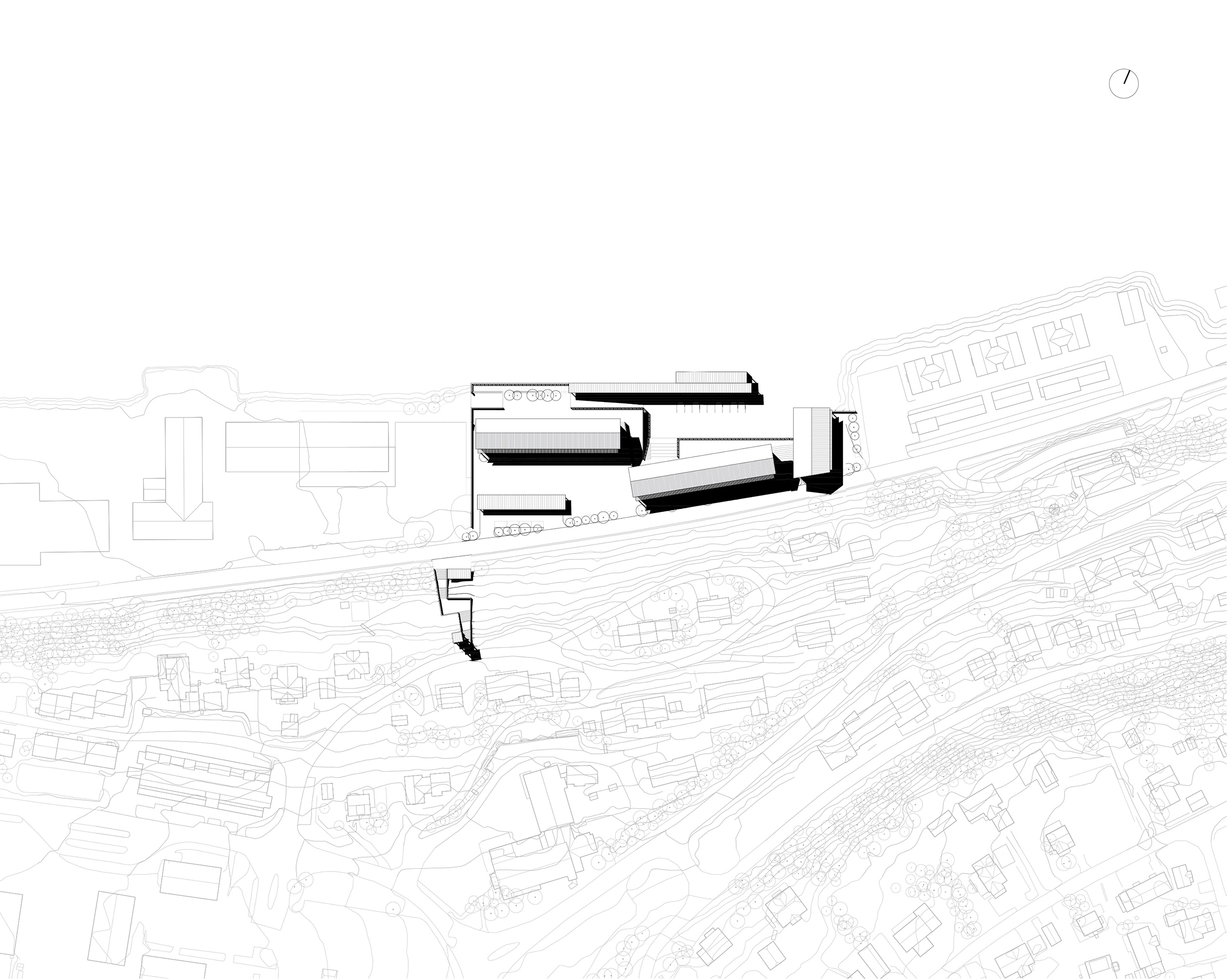

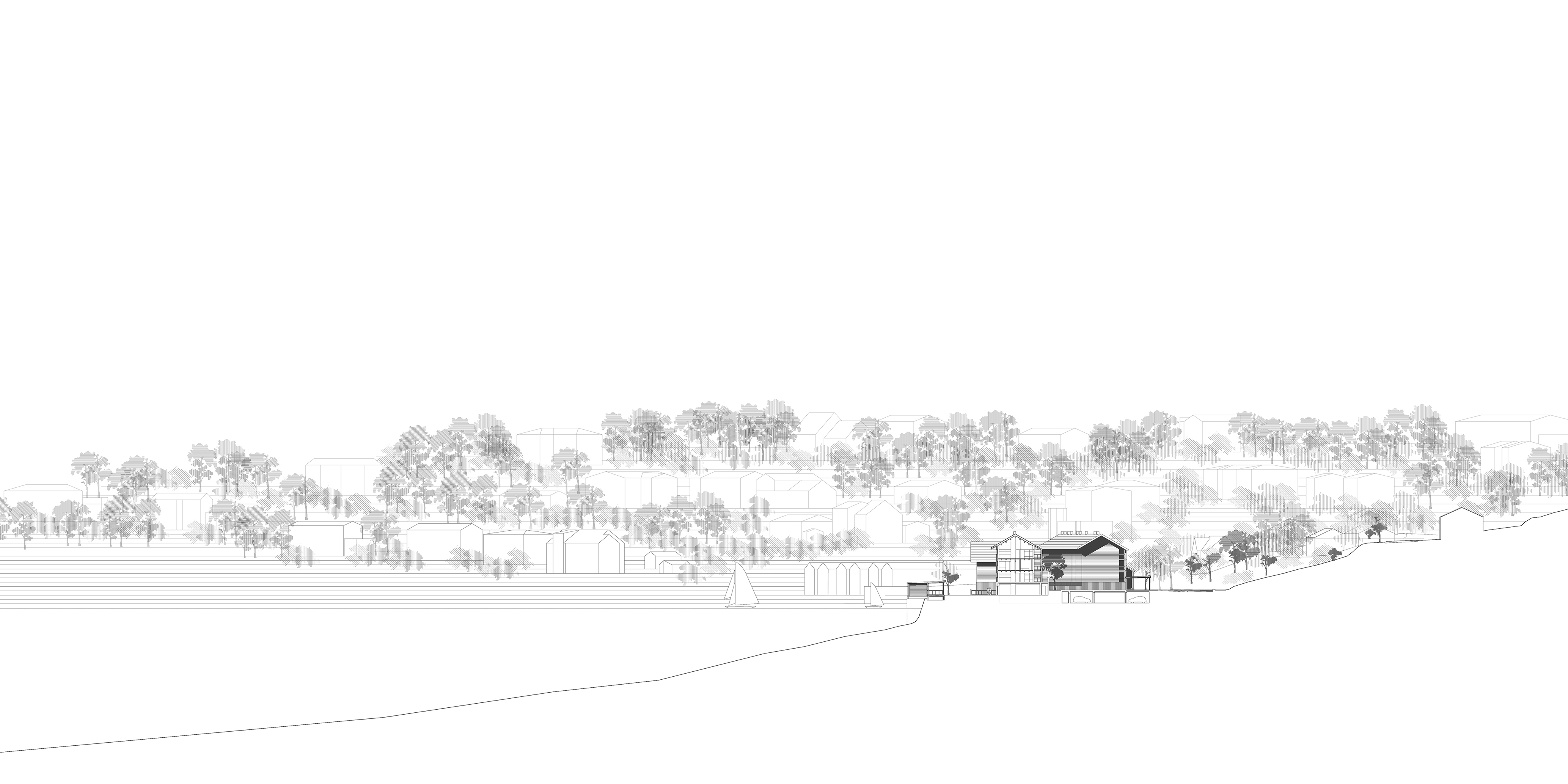

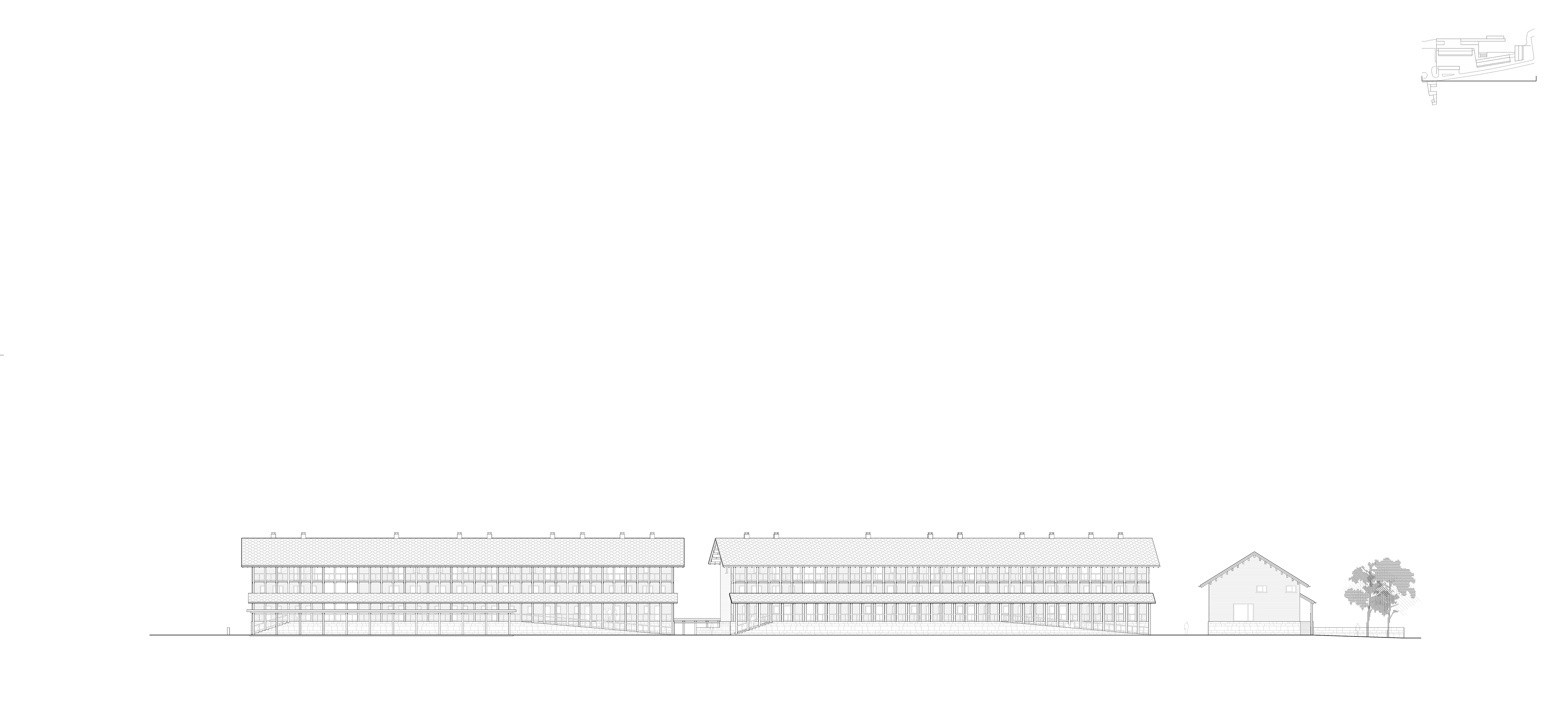

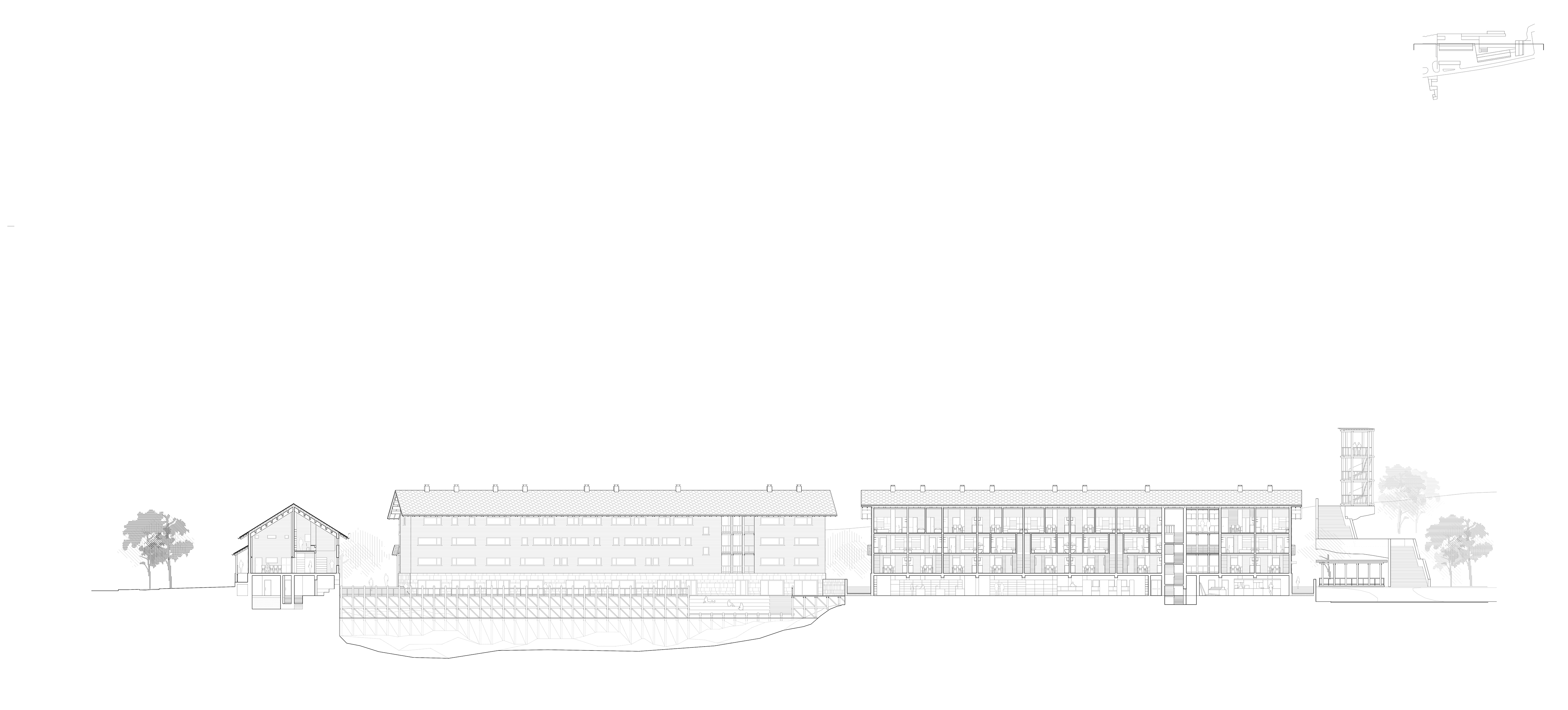

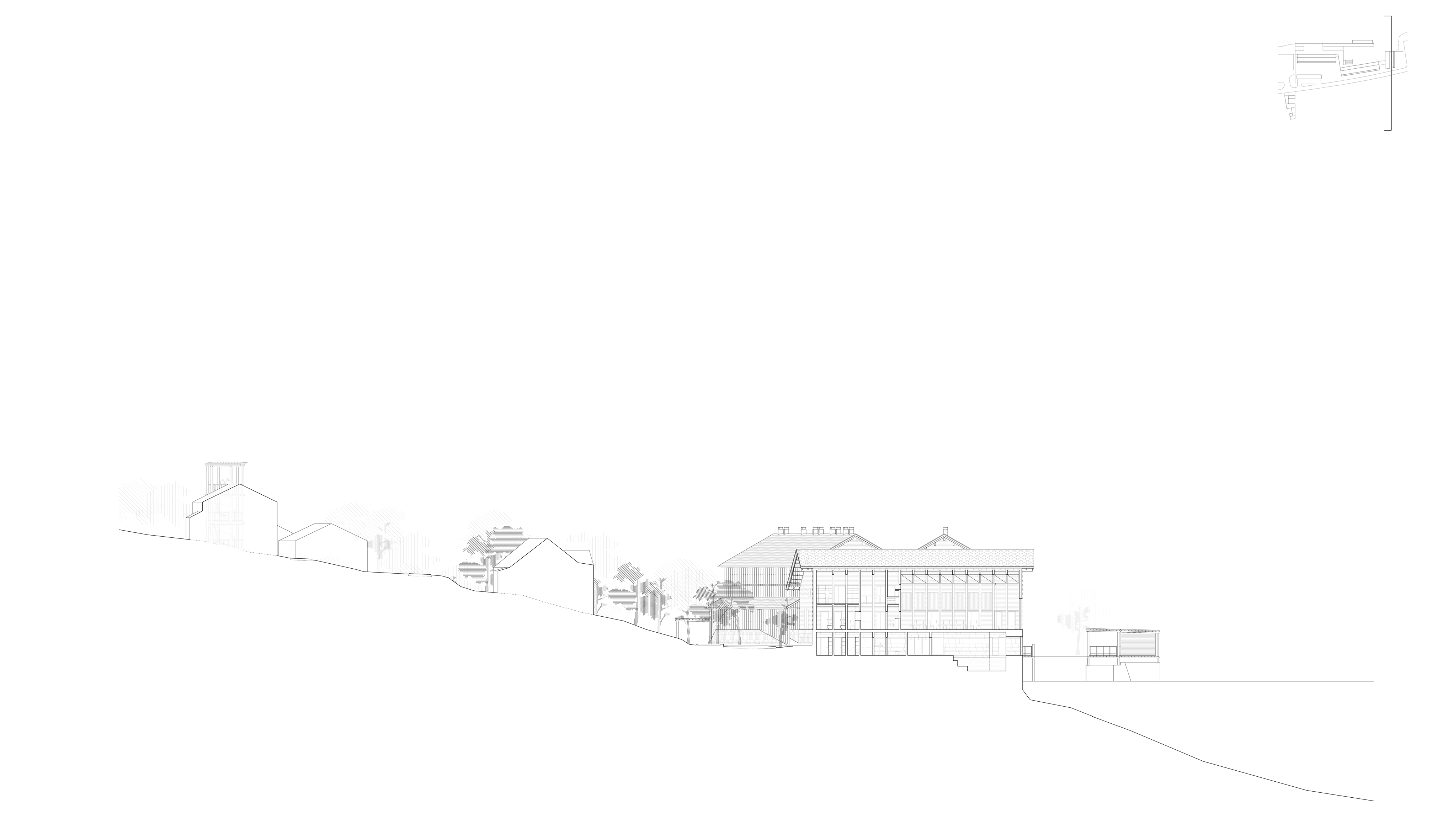

The project “Houses on the Fjords” is located south West of the town of Alta, in Norway. Alta is a small town with a population of about 20.000 people. It is characterized by an urban fabric made mainly of small wooden houses with gabled roofs, having a maximum height of two or three levels and small streets that adapt to the morphology of the territory. The planning underlying the urban fabric shows the intention of preserving the territory from the phenomenon of densification and to enhance, on the other hand, the relationship with the surrounding landscape and the need of intimacy and privacy of its inhabitants. Today the economy of the town relies on small and medium industry, on fishing and some activities related to the production of slate and wood, but also on tourism, which is made easier by the presence of an airport connection. The plot where the housing complex in question will be built is located near Bossekop, on the main road named Straindvein, which runs along Skiferkaia port for a while. The surface of the plot is about 4240 sqm with about 3500 sqm of building possibilities. A 4m height difference describes the section of the lot from the road to the sea level, while on the other side of Straindvein the orographic situation shows a town built on a high promontory open to the fjords and in a close visual relationship with the landscape. Near the area there are rare examples of medium-large industrial sheds, related to the activities above mentioned. The area under study was mainly used as an open-air deposit of slate labs.

TRADITIONAL BUILDING MATERIALS

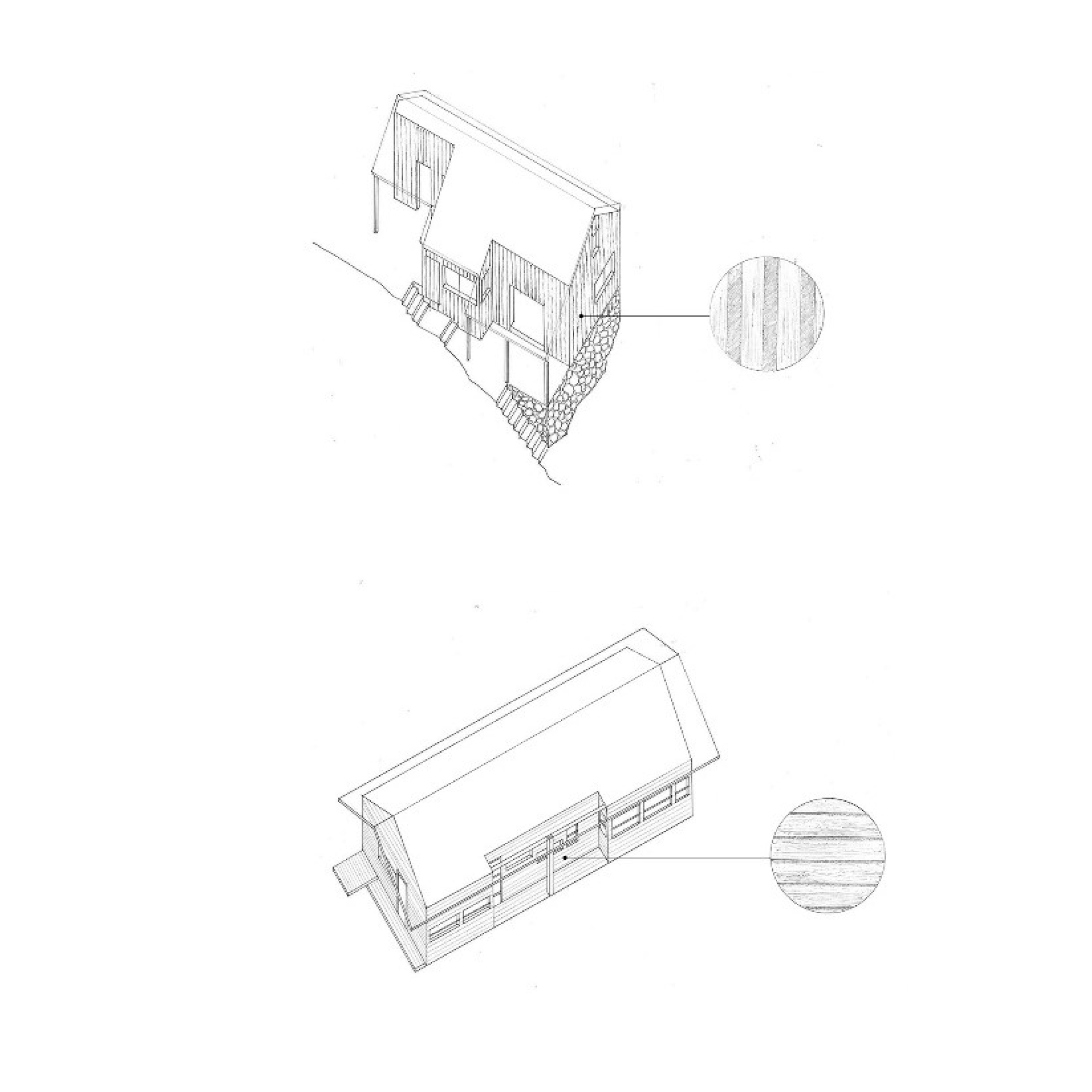

If we start considering the oldest anonymous Norwegian buildings, moving, then, to an observation of the vernacular houses in the Viking villages, up to the emblematic Stavkirker, paradigmatic models of a building technique that has no equal in the world, not to mention the extraordinary engineering of the Drakkar and the Knarr, we can certainly state that wood is the most widely used building material in Norway’s architectural history. The deep constructive wisdom of Nordic carpenters, their structural clarity, their knowledge of the material and respect for its properties have created a real art of building, consolidated over time up to recognize itself as an identity. The continuous observation of traditional Norwegian architectures and in this specific case leads us to consider a second building material, especially used in the base parts or in the coverings of the roof layers: slate. Alta is, indeed, one of the main slate extraction sites in the whole Norway along with Oppdal, in the central area. The building tradition of Norwegian houses shows in several project drawings and photos the walking surface isolated from the ground by wooden substructures or by stone bases upon which the structure is placed.

The stone base serves to better isolate the wood from the rising of water by capillarity which would otherwise damage the structure and, therefore, the static balance of the entire building.

CRITICAL REGIONALISM AND THE EXAMPLES OF SVERRE FEHN AND WENCHE SELMER

“The Tactile and the Tectonic jointly have the capacity to transcend the mere apparent of the Technical, in much the same way as the Place-Form has the potential to withstand the relentless onslaught of global modernization”.

K. Frampton, Towards a Critical regionalism, in Hal Foster, ed., The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Post-Modern Culture, London 1983

Critical Regionalism is the set of formative rules of an approach that the historian Kenneth Frampton brought to the attention of contemporary debate in 1984 thus providing an alternative to the widespread internationalism of our age. Its aim is clearly against adopting efficiency parameters in assessing architectural spaces and materials and in favour of the development of “a strong culture, full of identity, yet open to contacts with the universal technique”.

The implementation strategy of this approach is not attributable to a nostalgic-like feeling. It’s fundamentally based on the will to achieve a new balance between the product of universal civilization and the elements that can be derived from the characteristics of a particular physical place, drawing from the latter peculiar qualities, such as, for example, the tectonics used in traditional buildings, the topographic conformation, the characteristics of the openings (flush with the wall, set back, protruding, fitted with sunblinds or not, with a slot) and the perceptual relationship with the materilas used. Another fundamental aspect of regionalist poetics is, indeed, the use of materials capable of activating most of our sensory perceptions, not only those related to the aestheticizing image of contemporary “Ephemeral Architecture”. To this end the qualities of light and darkness will be considered, but above all the qualities perceived only by experiencing the space from within, that is, by the users:

“The heat, the cold, the flavour of the materials, the sense of humidity, the almost palpable presence of wood, where the body feels it belongs, the speed of our pace and the relative inertia of the body while crossing a plan, the echo and resonance of our steps”.

M. Heiddeger. Quote from Frampton: Costruire, Abitare, Pensare. 1954

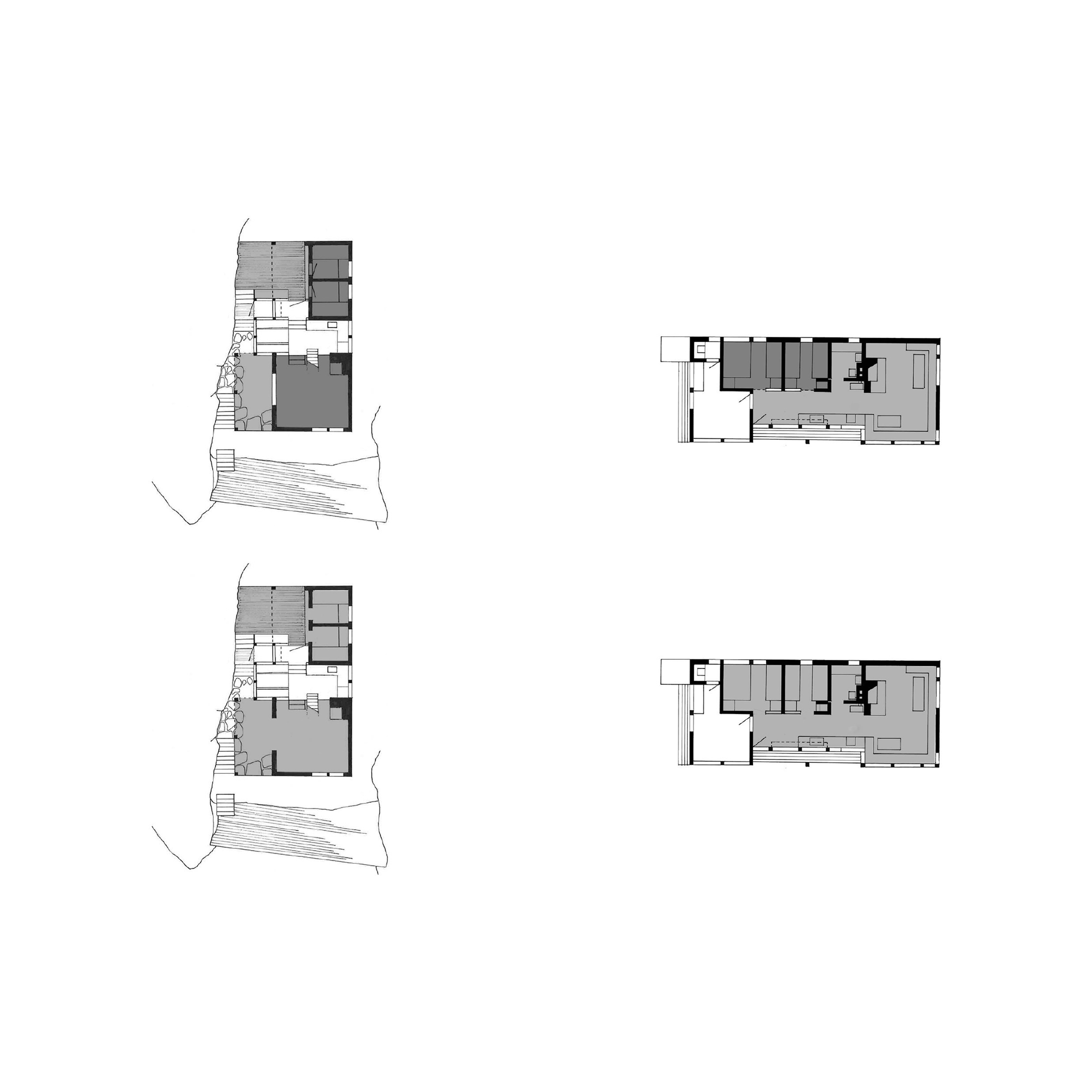

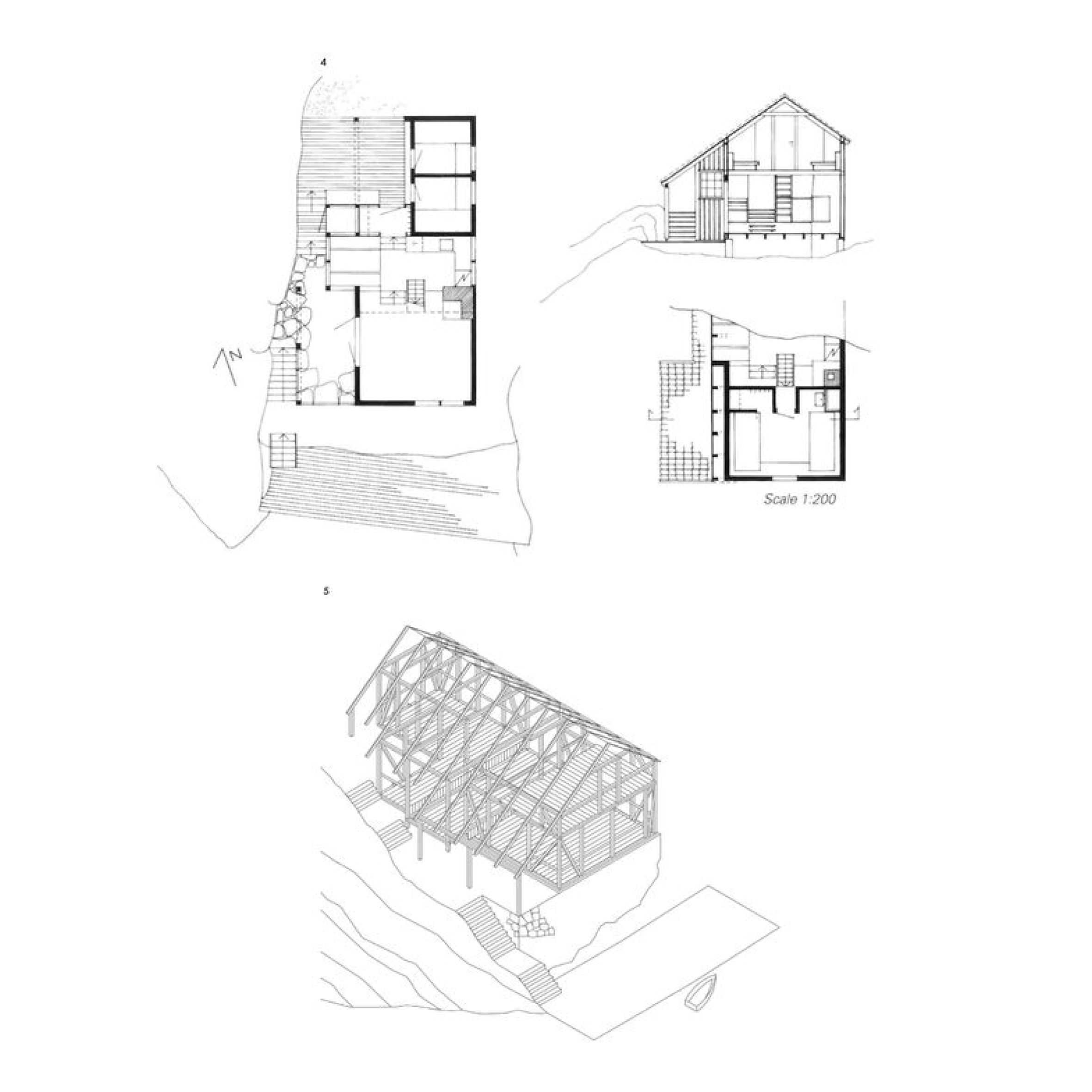

Tactile and tectonic are, therefore, the two lost qualities that Regionalist architecture intends to recover in order to activate a process of resistance to the technological imperative that mass culture has excessively introduced into contemporary culture. This process is aimed at stopping the loss of cultural identities and, on the other hand, at fostering evolution and progress, connecting them with the reach of traditions and the history of places. Along with the extraordinary work of the architect Sverre Fehn, there’s another, no less important, work that should be considered. We are talking about the houses of the architect Wenche Elisabeth Selmer, who graduated from the National Crafts and Art Industry School of Oslo in 1945 and from the National Architecture Course in 1946. The analysis and studies carried out on Selmer’s different typologies of houses were of fundamental importance for the development of the project as to the use of materials, tectonic parts and typological schemes. The plans of the Wigert Summerhouse in Brekkestø, for example, as well as those of Wohnaus Wenche and Jens Selmer’s one in Oslo or the Wohnhaus and Fotoatelier for Jim and Trine Bengtson in 1974 and the Hütte for Jan Herman and Birte Reimers in Sølbøseter, all share some repetitive elements which can be therefore considered, according to an analogic-comparative reading, typological invariants. One of these is certainly the fireplace, the heart of domestic space, usually made of bricks and placed within the living/dining area, just after a hallway. The kitchen is always open and communicates with the living room, while there is a clear separation between this area of the house and the sleeping area. The formal archetype takes up the type having a two-pitched roof made of wood with slatted covering boards vertically or horizontally arranged. The volume of the houses almost always consists of one, maximum two levels, with small-medium openings to preserve an internal condition that seeks a dialogue with the surrounding landscape through glimpses of the outside. Many of the examples analyzed use the basic solution with a stone base, testifying through their realization the effective efficiency of the isolation system from water infiltration by capillarity.