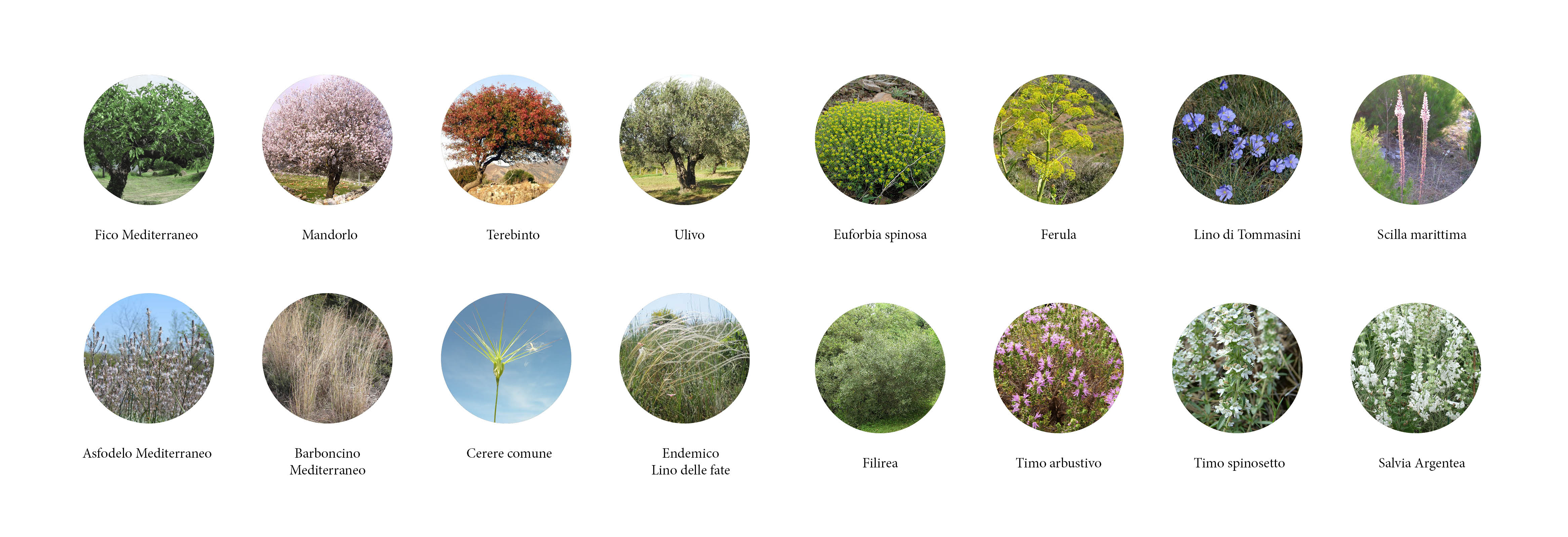

Located in Lama di Cervo, in the newly realized neighbourhood called “Trentacapilli”, South West of SS 96, which divides the city of Altamura (BA) in two, is La casa delle Ferule, the proposal for the new kindergarten and primary school. The urban context presents, in its close surroundings, houses mainly built in the last twenty years aggregated in a not very compact urban fabric and located on the edge of what constitutes the typical rural landscape of the Alta Murgia Park. We are on the edge of the built city, where concrete blocks, asphalt, terraced houses and the “pop-modern” villas come to an end and where the almond trees, ferule, terebinths, olive groves, Mediterranean figs and Lino di Tommasini are born; where the Endemico delle Fate whitens in the green. Along via Lama di Cervo, and even going down towards via Pietro Colletta, we already find corrugated layers of calcarenites emerging from the fields and seemingly rising from the earth, half-length, as if they had always been there, dry stone walls, and, following on, cascine, masserie and jazzi.

The site of intervention, extended for a gross surface area of about 5.250sqm, is classified within the P.R.G. as “C2 expansion area”. The residents of the neighbourhood are mainly young families with school and preschool-age children who are currently forced to travel by car to reach the nearest schools due to multiple problems: among them the most important is the risk posed by the crossing of the SS96 and the lack of infrastructure for slow mobility. The neighbourhood is also affected by a shortage of public green spaces equal to about 7sqm for inhabitant less than the expected amount, and this despite being close to the countryside and even though the P.R.G. has set a standard of public green equal to 9sqm for inhabitant. Fortunately, the Integrated Sustainable Urban Development Strategy (SISUS) is already providing for an improvement of this provision, but this does not appear to be enough, especially if we consider this as a place where children will grow up and learn to know themselves through their own territory and the contact with nature.

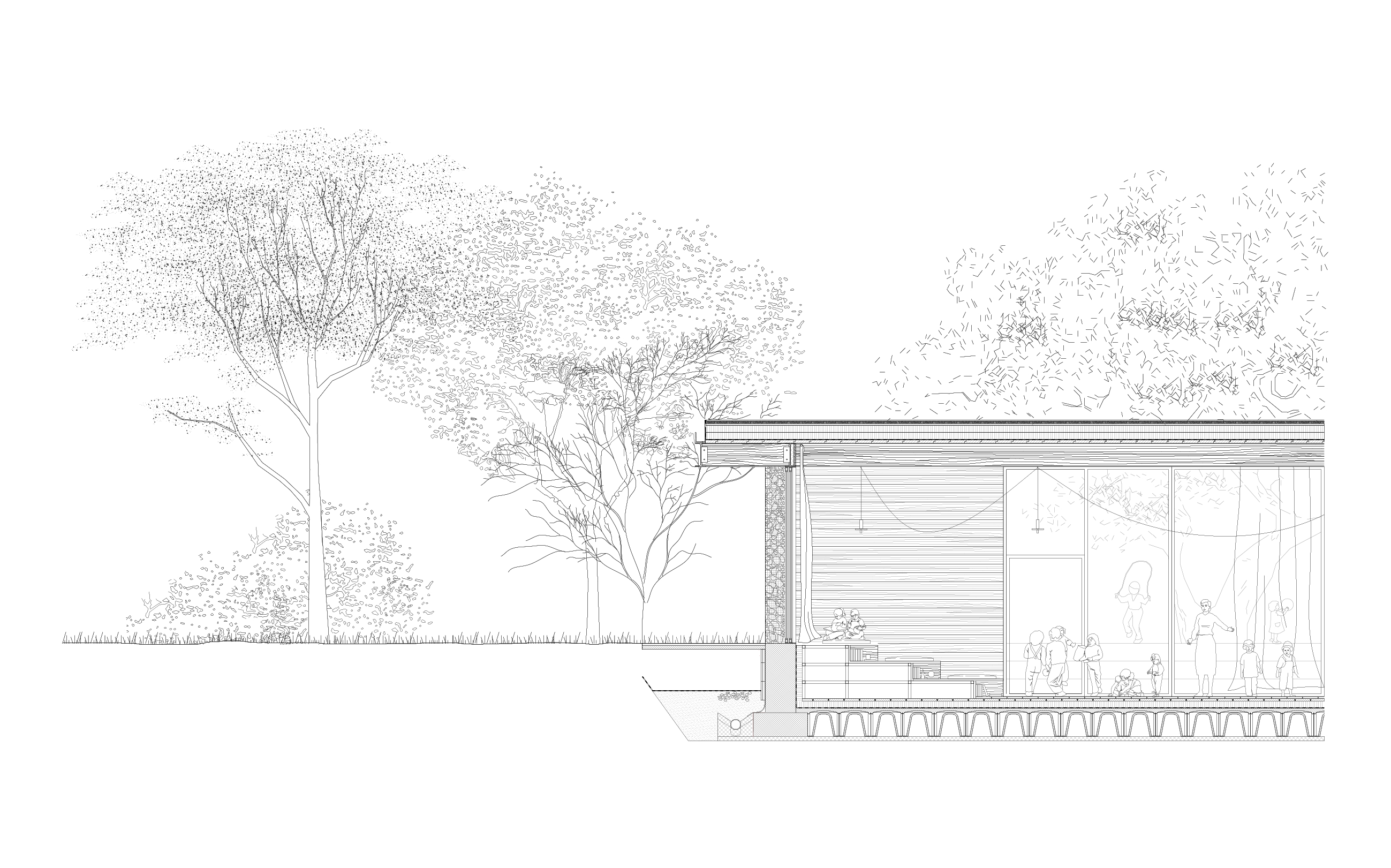

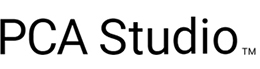

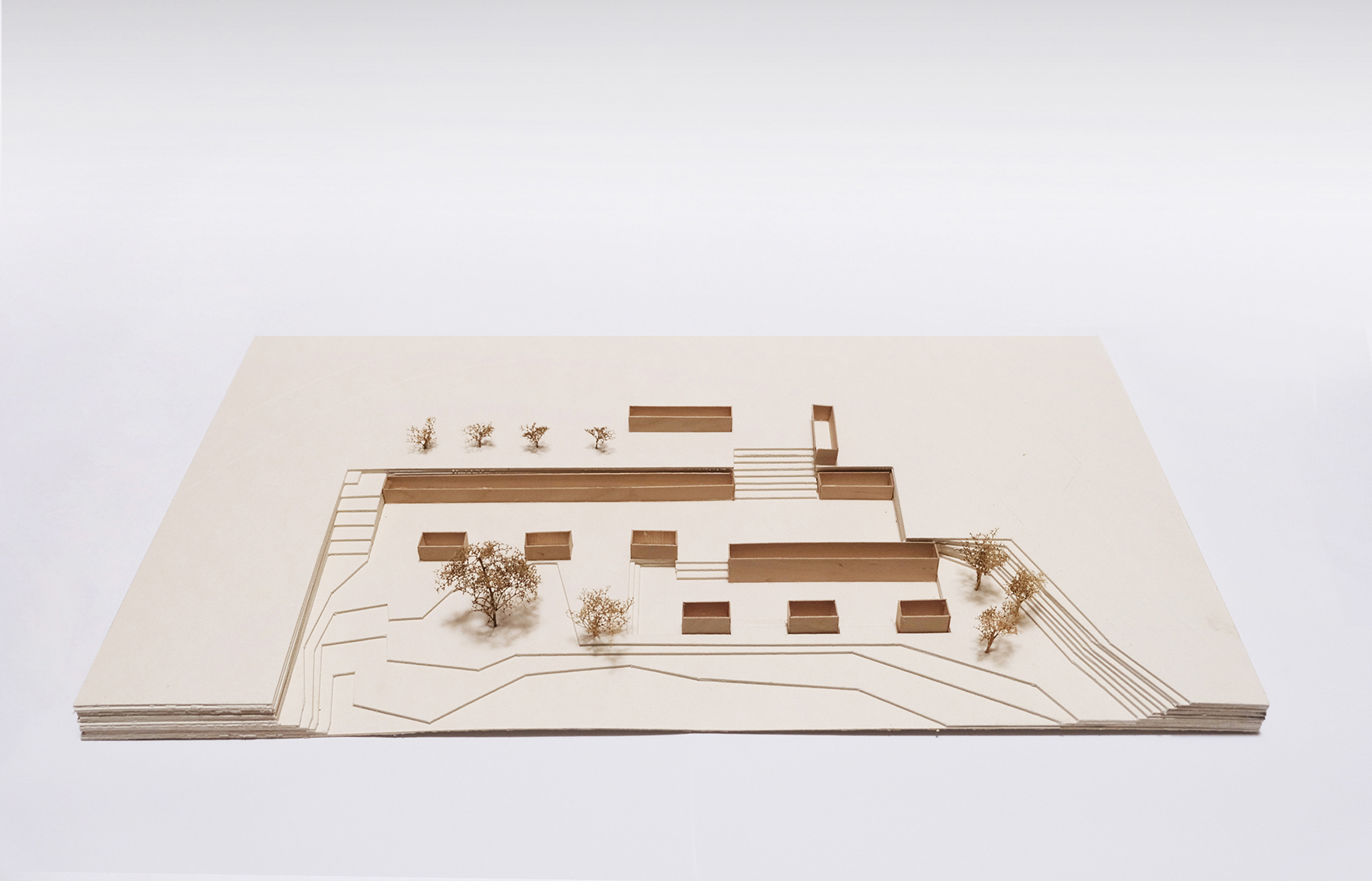

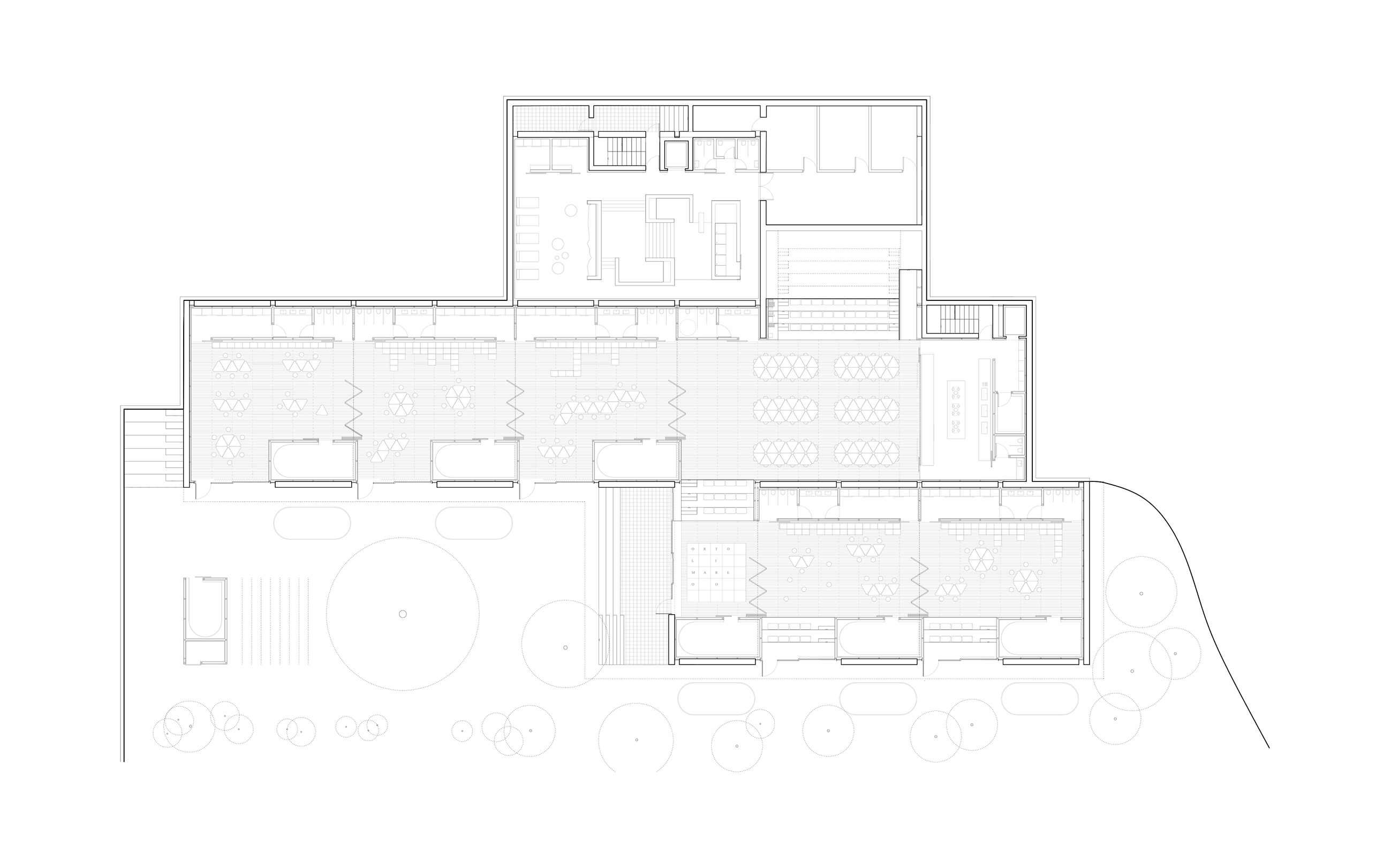

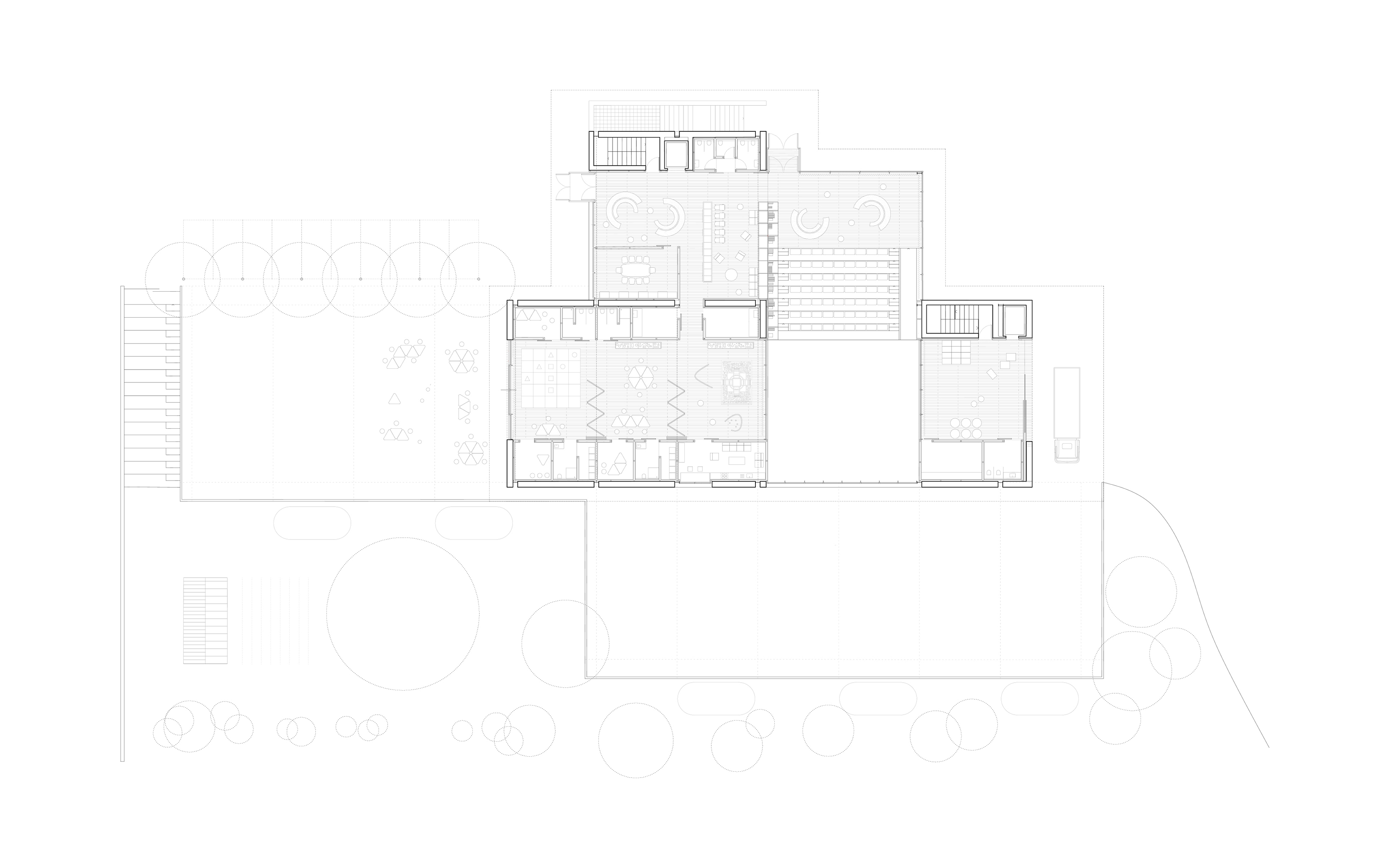

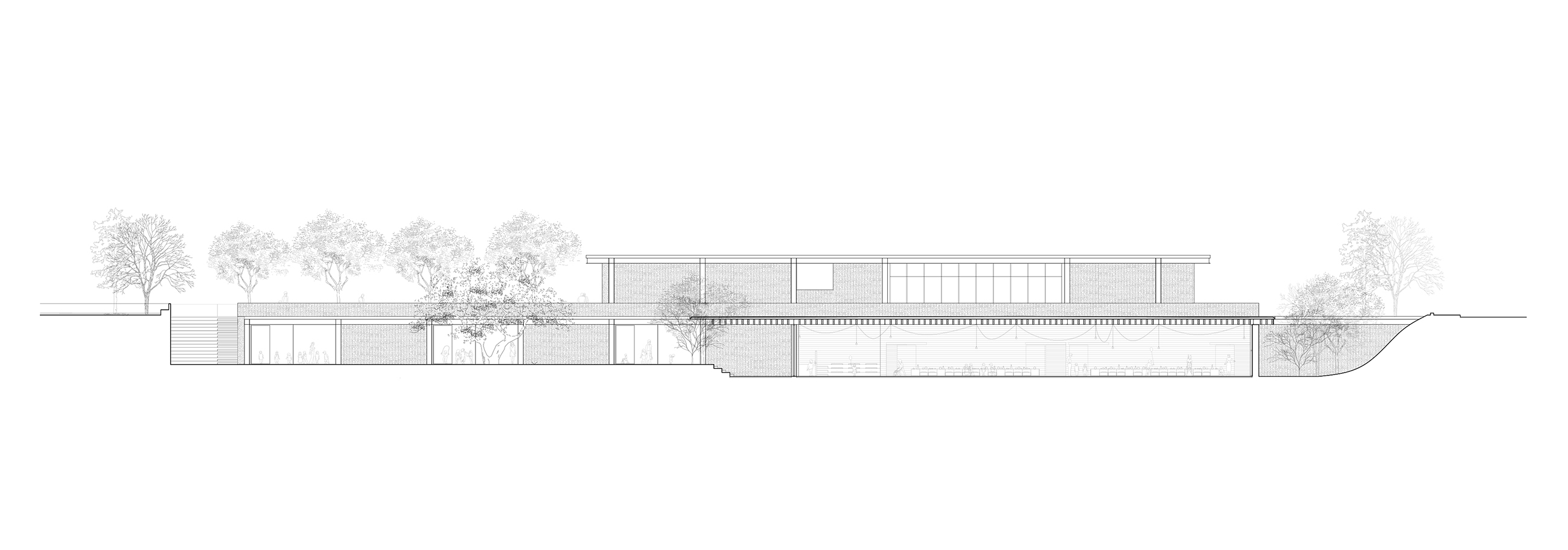

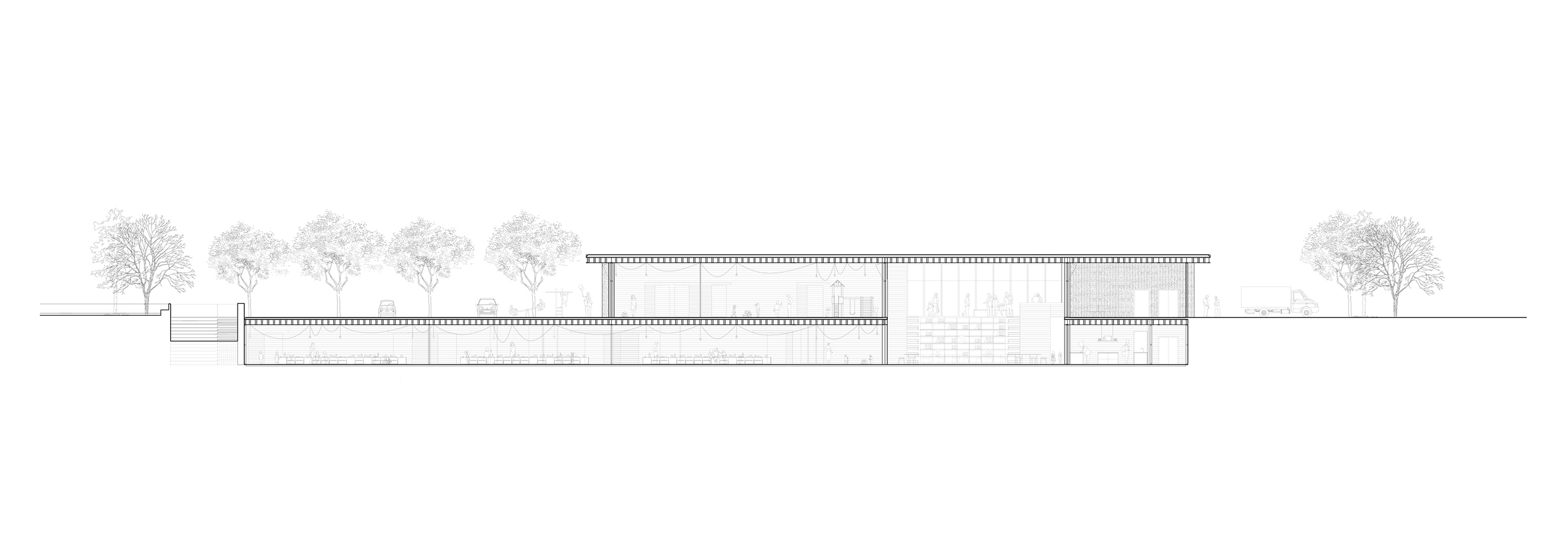

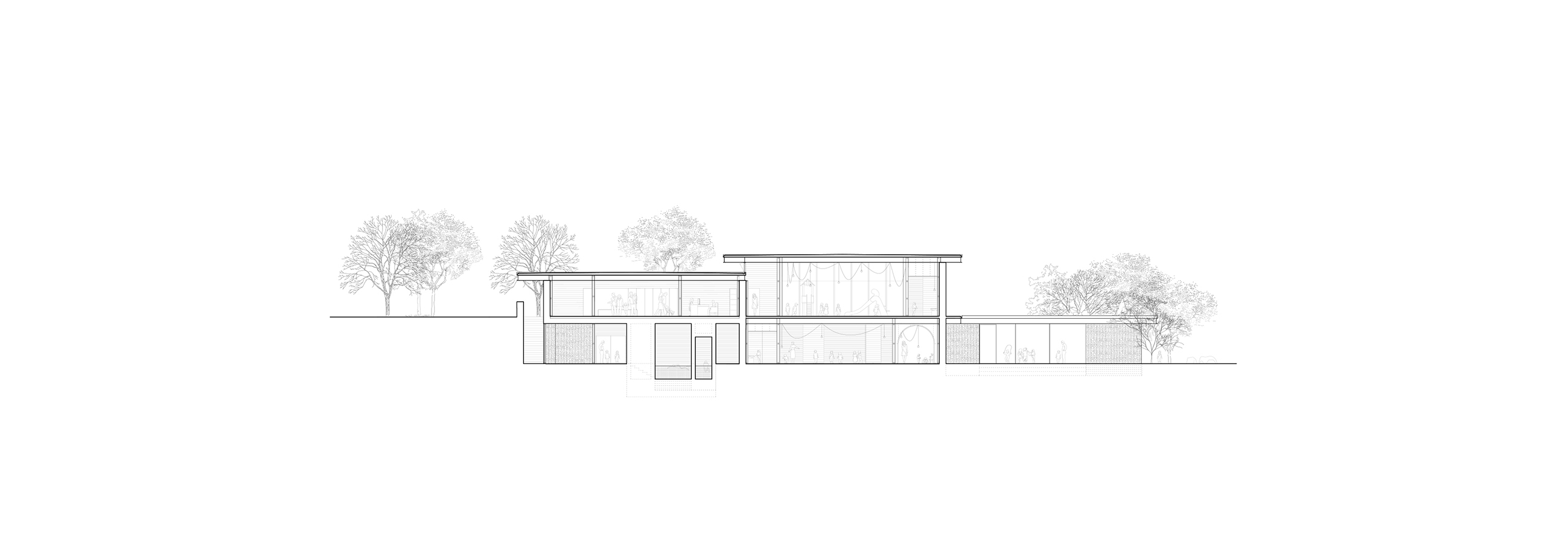

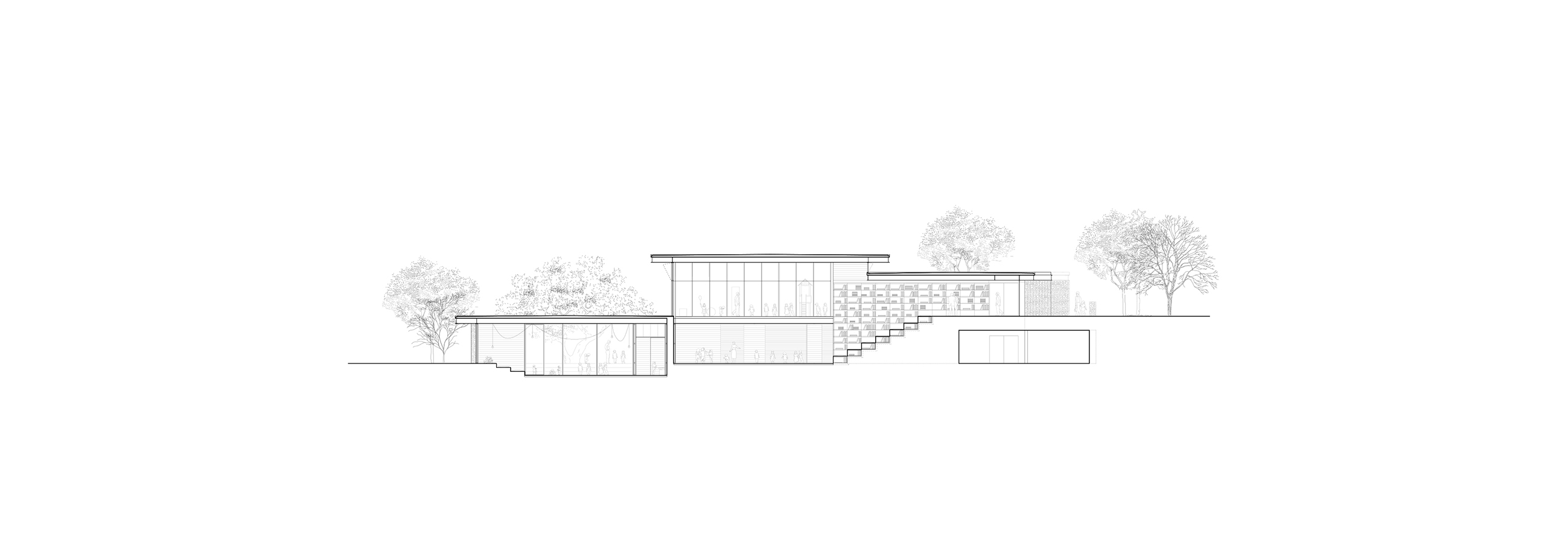

The study area is, at present, slightly lower than the road level (Min.1.30m / Max 2.50m) and served by two main axes (respectively Via Caduti delle Foibe and via Giovanni Gentile) with a road section of about 9m each and two-way traffic. The alignment of the lot is optimal, SOUTH / SOUTH-EAST, which is extremely important for issues related to the orientation of the school spaces and their natural lighting. The difference in height described above, guided the design choices towards the extension of the street level within the plot with the aim of giving space to a new urban square juxtaposed to the main entrance of the school and oriented towards the park (this space is not only available as a parking lot, but also as a public square serving the neighborhood for concerts, markets, open-air cinemas or other collective activities). On the “artificial plane” of this “new neighborhood square”, the quadrangular volumes containing the spaces of the nursery and the “sezione primavera” were set up, flanked by those of the secretary / administration. On the lower floor, instead, passing through the large common “Agorà” (The Library / Auditorium) illuminated from above through a double-height space, we find the functions relating to the sections of the kindergarten, with the canteen, the kitchen, the gym and a small swimming pool. Particular attention was paid to the design of open spaces, not only with regard to the square at the entrance of the building, but also, and especially, to the design of the green spaces. Every species included in the project is, in fact, native of the place and integrated within the area called “Bosco della Murgia”, directly communicating with the sections of the building in order to guarantee a direct internal-external relationship from every corner of the classrooms. It is here that the great Mediterranean fig tree finds its place, bearing its fruits and lending its large shade for outdoor readings of fables and fairy tales. This is where, in the small botanical garden, the children can learn that caring for the earth can bring wonderful fruits. This is where the almond tree, positioned on the side of the “small theater”, outdoors, can tell the story of the onset of spring. It is here that the Terebinth colors the sky of red matching the poppies on the meadow. This is where the ferules sprout together with asphodels, silver sage, spinosetto thyme, spiny euphorbia and sea squill.

In any possible way, the project seeks the landscape, in the desire to integrate it, to absorb it, to look for the core identity of this territory, to give it back to the children, to give it back to the future.

Construction technology

Starting from the modern era, and more precisely from the 16th century, the builders of military or hydraulic works, especially in Italy, began to employ on a large scale construction systems used to retain the ground and based on the stacking of large baskets first, and of metal mesh containers later. This practice, which is particularly effective and easy and quick to carry out, spread rapidly with the name of “gabbioni” (gabion) system. The element thus composed is extremely robust, with good resistance to static loads and moderate resistance to bending, it is susceptible to numerous variations in dimension, colour and materials and by stacking can create self-supporting structures which are resistant by gravity. The gabion blocks are a highly modular technology, more rigid and easier to displace than traditional ones and are easily suitable for the construction of infill walls but also self-supporting walls up to 7 meters high. The material expressiveness of a wall built in gabions is that of a wall with an irregular dry technique, perceived through the metallic filigree and marked by the subtle discontinuities between the modules resting on top of each other and next to each other. It is easy to imagine, therefore, how, in fact, this new way of conceiving the construction of walls expressed by the use of “gabions”, in its irregular, expressive surfaces, made of chiaroscuro, masses, voids, setbacks and projections, is traceable, by analogy, to the rural architectural tradition (referring to the UNESCO Heritage dry stone walls that characterize the identity of the entire landscape of the Alta Murgia Park) and is viable to be re-proposed in the project, for the construction of the new Polo per l’infanzia of Altamura. Alongside these formal and sensorial aspects, certainly susceptible to further developments in the current building culture, the use of gabions presents a series of technical and performance characteristics that are consistent with some fundamental instances of contemporary architecture: the production and installation of these elements have very low energy footprint and are environmentally friendly and, thanks to their original ability to combine drainage capacity with modest water retention properties, they can become a good habitat for the development of a spontaneous or induced vegetal biocenosis. Gabions are permeable to air (which is why they adapt perfectly to “ventilated facade” systems) and, at the same time, generally have high thermal inertia; they are cheap, easy to transport, durable; they do not require maintenance, are modular, can be dismantled and can be reused; moreover, even from their first manufacturing, recycled materials can be used for their filling. As can be seen from this short description, each choice, is not only supported by obvious, albeit fundamental, economic-managerial parameters, but is also strictly connected to a special focus on the use of local materials, easily available on site, and which bring the expressive potential of the landscape they belongs to. The architecture of the facades declares the main structure (metal frame with IPE profiles) making it intelligible in the succession of infill walls made with the gabions of local stone. The internal envelope, on the other hand, creates a space completely made of wood, satisfying the dual purpose of having, in the first place, a material that efficiently retains the heat inside the rooms avoiding excessive thermal dispersions towards the outside and, in the second place, an adequate response to the safety and comfort needs, that are to be foreseen for the well-being of the children, and to the psycho-perceptive ones that are inherent to the kind of space that an Innovative Childhood Center of today should aspire.

Pedagogy

In the book entitled “Self-education”, Maria Montessori tells that, to those who asked her how the sociability could develop among children if they worked alone, she replied that the traditional school was a place of regimentation “where all children do everything at the same time, even going to the toilet… ”. And she continued stating that “the society of children is made upside down compared to the common one: here sociability involves free and fair relations of courtesy and mutual help, although everyone minds his own business: there, on the other hand, sociability involves the commonality of postures of the body and the performing of uniform collective acts, but with the abolition of any pleasant or courteous relationship: mutual help then, which in the other society is a virtue, here is the greatest crime, the worst form of indiscipline ”.

The traditional school model is at risk of corroborating an individualistic model, which is made clear by the organization of space, where we normally find single desks lined up in front of a teacher’s desk, behind which the educator speaks and asks the students to perform the same tasks at the same time, using the same methods and the same tools. It is a mechanical action that considers everyone as equal and leaves very little room for freedom. The appearance is that of collaboration, because they share an equal task, however the work must be strictly individual in the sense that it ultimately denies any connection with classmates. But for Maria Montessori, “collaboration” does not mean doing the same things nor it necessarily implies working in a group. In the society of adults, collaboration arises, for example, in contexts where a team is formed to solve a task and each one of its members is given a specific role that he carries out on its own, and, at the end all the contributions are put together: different activities are thus defined that value the skills of each one, to create a product that is not just the sum of the different elements, but the result of a joint commitment. The Italian pedagogist highlights the theme of community even when she focuses on the importance of mutual aid, especially between older and the younger children: “Our schools have shown that children of different ages help each other; the little ones see what the older ones do and ask for explanations, which they gladly give ». This is a perspective that highlights how proximity in age can sometimes better help in learning and create a climate for personal and common growth. In fact, she writes: «It is a true teaching, since the mindset of the five-year-old child is so close to that of three, that the little one easily understands from him what we would not be able to explain him…».

But the support for all this is space.

To make all of it possible, careful planning is required that adopts a flexible, modular approach to space and integrates modular furniture, desks and chairs that can be easily moved and adapted to any configuration and activity. In La casa delle ferule the principle of spatial modularity implies that each classroom can be extended to 2 or 3 by means of movable panels (on which signs, calendars or drawings can be hanged), with the aim of encouraging relationships between children and developing creative dynamics even in extended group activities. The project for the new Childhood Center, therefore, embraces the needs of the new pedagogy and prepares the space to accommodate inclusive dynamics starting also and above all from the involvement of families, relatives, local artisans and artists. The aim is to create the opportunities that make it possible for the child to experience the world, which encourages him to recognize his hardness and unfathomability, which helps him to meet / collide with his limits, while nourishing his curiosity and wonder for the things that populates the world, thus stimulating creativity through the act of “making”.

“Is it worth it for a child to learn by crying what he can learn by laughing?”

Gianni Rodari